Lack of Black Reporters in Local Newsrooms

NBC4 Los Angeles reporter Beverly White (Photo / NBC4, illustration Doug Forbes)

LOS ANGELES — When Fay Jackson and her family landed in Los Angeles by way of Dallas in 1918, the world was in a tailspin. The same strand of influenza that terrorized American doughboys battling hostile troops in “The War to End All Wars” was on its way to killing roughly 3,500 Angelinos, according to The Los Angeles Daily Times.

The Times also took aim at America’s free speech crusades, including the Sedition Act of 1918, which punished anti-war activism, and the plight of steadfast suffragettes who inched ever closer to the ballot box.

Los Angeles Daily Times (now the Los Angeles Times) circa September 2018 reported on influenza

The Times circa January 1918 reported on suffrage

Jackson took a keen interest in exploring people and places that defined a tornadic era in world history. She earned a degree in journalism from the University of Southern California and soon became a newshound who secured confabs with kings and emperors, cultural icons, community ringleaders and commoners.

However, she would never attach her byline to the Los Angeles Times or any other major masthead. After all, this was early 20th century America, and Jackson was black.

Undaunted, she became America’s first black foreign correspondent and Hollywood correspondent, and the first black person to launch an intellectual newsweekly on the West Coast.

Fay Jackson (Photo / University of Southern California Libraries)

Jackson also fused her historic reporting exploits into fodder for a weighty mid-career speaking junket. Upon the tour’s opening at Second Baptist Church in the heart of Los Angeles, she said, “As the first American Negro journalist to be appointed and maintained over a period of time as Foreign correspondent for the Associated Negro Press … I do not emphasize the ‘first’ to bring myself any special glory. It is a matter that should have been attended to long before now. I knew that over 400 million colored people are subjects of the British Empire … there ought to be the same news value for American Negro readers.”

Jackson’s legacy would not be the mallet that would smash the glass ceiling for a surfeit of black journalists to follow. In fact, the number of black people in today’s newsrooms — statewide and nationwide — is trifling at best.

California serves up the world’s fifth largest economy. Los Angeles ranks eighth in the number of black residents for cities with populations over 100,000. The Los Angeles Times is the largest metropolitan newspaper in the country. And, the Los Angeles television market ranks second behind New York.

Nonetheless, only six percent of statewide news jobs are held by black people, according to annual census data from the American Society of News Editors (ASNE). A scant six percent of the Los Angeles Times news staff and three percent of its newsroom leaders are black, according to ASNE

In 1933, Jackson helped two friends launch a black-owned weekly called The Los Angeles Sentinel. Author and Guggenheim Fellow Douglas Flamming penned a book titled “Bound for Freedom: Black Los Angeles in Jim Crow America,” in which he said the Sentinel was “easily the most sophisticated race paper ever offered to the community.”

Still operating today from the edge of South-Central Los Angeles, the Sentinel serves “one of the most lucrative target markets in the U.S.,” according to its current profile.

The Sentinel’s pronouncement stands in stark contrast to the reality at hand. According to a 2017 UCLA Labor Center report titled “Ready to Work, Uprooting Inequity: Black Workers in Los Angeles County,” the region’s black population has been dwindling since the 1980s, with more than 100,000 black residents having deserted Los Angeles due to unaffordable housing, lackluster schools, low wages and job losses.

Los Angeles Sentinel headquarters (Photo / Doug Forbes)

Danny Bakewell Jr. is the executive editor at the Sentinel and owner of Bakewell Media. “For newspapers to understand what’s happening with these communities, you have to have some reporters who look like us and who understand us,” he said.

“The first thing that any good reporter should do is to get on the street, meet community leaders, build trust and understand the trials and triumphs of the communities that they report on.”

Bakewell said that very few black people are “at the top of the newspaper food chain,” therefore, executives pick from their inner circles.

In order to broaden opportunities for aspiring journalists, the Sentinel offers an intern program popular with colleges nationwide, including Notre Dame, Northwestern and USC, he said. “Our interns are not getting coffee and answering phones. They are reporting and editing, almost from day one.”

The increasing evaporation of traditional news jobs nationwide does not bode well for an already piddling pool of black journos. According to a 2017 report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, newspapers emptied half their staffs from 2001-2016.

White faces continue to dominate the White House briefing room.

White House press briefing, 2018. (Photo / White House Correspondents’ Association)

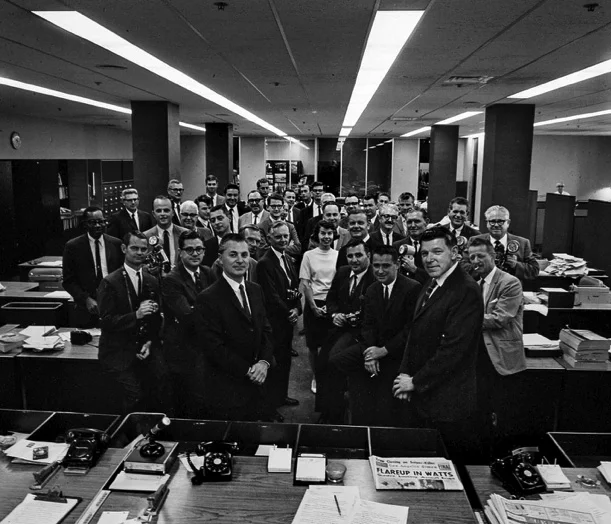

The New York Times did not hire a black reporter until 1945. The Washington Post waited until 1952. And while the Watts Riots of 1965 poisoned Los Angeles with racially charged venom, The Los Angeles Times was without a single black reporter on its roster.

A black ad rep named Robert Richardson was tapped for the titanic task. With no experience, Richardson used pencil, paper and pay phones to chronicle mayhem from deep inside the lair. A year later, that same Los Angeles Times team received a Pulitzer Prize for its accounts.

Pulitzer Prize-winning team at the Los Angeles Times, 1966 (Photo / Los Angeles Times)

Journalist Sylvester Monroe said that similar happenstance had an equally profound effect on his life.

Monroe said he was born into a Mississippi sharecropping family that relocated to Chicago in 1951, during the heart of the Great Migration. A ninth-grade English teacher recommended him for placement in a nonprofit program that populated prestigious boarding schools with promising minority youth. This good fortune paved the way to a Harvard education and a rich career in journalism, he said.

Following an internship at the Chicago Defender, the oldest African American newspaper in the city, Monroe worked as White House correspondent and Boston bureau chief for Newsweek, national correspondent and South bureau chief for TIME Magazine and deputy managing editor of the San Jose Mercury News.

“After Martin Luther King was assassinated, more black folks received opportunities to join newsrooms – the nation and newsrooms responded to the need,” he said. “But advancement was and still is a whole different story. We were not sent up the ladder. And with the advent of affirmative action policies, many white people thought we were taking something away from them.”

Larry Wilson agrees. As public editor for San Gabriel Valley Newspapers, the veteran (white) journalist said, “This (dearth of black journalists) is a tragic story. There was a time when it was very important for newsrooms to have affirmative action hiring standards for hiring black reporters. In the economic meltdown, I’m afraid that disappeared.”

The Civil Rights movement, affirmative action and the race riots of the late 1960s forged new opportunities and new concerns for black journalists.

In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson assembled the Kerner Commission to investigate cause-and-effect of “The Long Hot Summer” – a nationwide spate of race riots – and establish recommendations to mitigate the strife.

According to the Commission’s findings, journalists “tried” to give a balanced account but “failed to report adequately on the causes and consequences of civil disorders and on the underlying problems of race relations.” Media gatekeepers were advised to expand coverage “through permanent assignment of reporters familiar with urban and racial affairs” and to “recruit more Negroes into journalism.”

Merdies Hayes said he has vivid memories of the riots. A teen in the 60s, he said, “As the Civil Rights Act came into play and the riots and the assassination of Dr. King tested the nation, you began to see more stories about black experiences from black reporters.”

After earning a degree in journalism at Pepperdine University in 1979, Hayes said, “I was the only black person on the news staff at most of my earlier jobs.”

The Los Angeles Times hired him as a general assignment reporter in 1986, after which he became an editor. He said, “Mr. Chandler (former publisher) never had many black people on his staff.”

A recent USC Annenberg School Fellow and current editor-in-chief at Our Weekly, Hayes said that the Black Press emerged from a media structure that either outright thwarted black inclusion or wrestled with the prospect of hiring black reporters who would subsequently prefer to square their lenses on black-centric content.

Hayes said that he does remember a Times program called Metpro – instituted in the 1980s and operating today – primarily designed to boost diversity. “Recent grad minorities with journalism degrees were recruited into various apprenticeships, such as covering local communities and practicing with strict professional reporting standards.”

However, Hayes said that converting internships into employment is not translating the way it should. “The truth is, we don’t need a black person to report on a fire or a white person to report on a fire. We simply need a good reporter,” he said. “I have known plenty of black associates who had to move to other markets or out of the profession altogether for lack of further opportunity and earning potential.”

Los Angeles Times headquarters (Photo / Doug Forbes)

Journalists face “relatively low pay” with “constant deadlines and long hours,” according to an analysis by 80,000 Hours, a nonprofit employment research group.

According to the United States Department of Labor, the median annual journalist salary is slightly more than $40,000 or under $20 per hour.

Monica Williams grew up in Detroit where the mean hourly wage is now $5 more than that of a journalist. Williams’ initial fascination with journalism was not tethered to money, largely because she was just 13 years old when the Detroit Free Press published her review for the Sunday book section, she said.

Williams has since worked as an editor, reporter, manager and digital designer for large-market media ventures, including the Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, Detroit News, 2018 Winter Olympics and a newspaper outpost in Seoul, South Korea. She currently serves as magazine editor and training/education manager for the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ).

SPJ was founded in 1909 to “improve and protect journalism.” The nonprofit supports 7,000 members nationwide. In March of 2018, SPJ hired its first black executive director, veteran journalist Alison Bethel McKenzie. In an effort to further cultivate organizational diversity, McKenzie has since hired two black staffers: Williams and career newsman, Rod Hicks.

“SPJ was started as a white male fraternity and has always been one, until now,” Williams said. “Like Alison (McKenzie), those of us with considerable experience must reach back and engage, mentor and afford opportunities to deserving people with unique perspectives.”

While a college freshman, Williams said she received such an opportunity as a copyediting intern at the Philadelphia Inquirer. “The program was founded by black reporter Acel Moore who received a Pulitzer Prize and a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard,” she said.

Moore realized there were very few minority copyeditors, largely because the job was the last line of defense at a paper, said Williams. When she became a copyeditor years later, she said it was her proudest professional moment.

Rod Hicks’ journalism career tracks from New Jersey to Michigan where he led a large staff as editor for the Detroit News. Hicks most recently served as an editor at the Associated Press in Philadelphia.

As SPJ Journalist on Call, Hicks said his job as both educator and mediator is to improve public trust and balance in media by fostering a more productive dialogue.

“One of the newsroom managers I recently spoke with told me that funds for hiring are tighter than ever. A lot of decision-makers say they want to increase the number of black reporters, but the results don’t reflect the promises.”

When positions open, he said, papers draw from existing relationships rather than sourcing new ones. “If top people in news organizations make a commitment to diversify, it’s more likely to happen.”

Andre Coleman is the deputy editor of the Pasadena Weekly, a 34-year-old paper targeting the San Gabriel Valley. Coleman said that money was not an issue when he got into the profession 30 years ago, but it is now, especially for black people who want to own and operate news ventures.

“If our small weekly can’t afford to hire reporters who we desperately need, middle class black people like me will find it impossible to own or operate a paper the way they want to.”

Coleman said that black journalists should not act with a herd mentality but should instead rely on their “individual voices” to change perspectives and thereby assume leadership roles.

Andre Coleman, deputy editor of Pasadena Weekly (Photo credit / Doug Forbes)

“For a long time, African Americans didn’t want to be cops because of the way they had been treated by cops. But then they began to realize they could change that by becoming a cop. I think journalism is the same way. We can change the perceptions if we are telling the story.”

Over the course of 40 years, Beverly White has earned numerous awards as a general assignment reporter telling stories for CBS, ABC and now NBC4 in Los Angeles. White has been on the frontlines of high-profile wildfires, hurricanes, mudslides and mass murders.

“White folks are not asked to cover white news. But folks of color are often sucked into a vortex.” White said she has been incredibly proud to work in newsrooms with a wide range of storytellers, but she is astounded by the lack of black newsroom staffers in one of the largest media markets.

Young black students need to remember that journalism is an important community service, she said. “My job as a journalist of color is to flip the script – to attend countless career days and educational events and tell young black people they can do it, but they must be prepared to work twice as hard and be twice as good.”

White said that the principal challenge is simple: a crippling lack of exposure. “If aspiring black journalists don’t see us, how can they be us?”